True Crime in the Great Outdoors

The most shocking crimes from national parks, camping trips, backpacker murders, and hiking incidents

The Starved Rock State Park murders

Revised October 2023

On March 14, 1960, the bodies of three women from the Chicago suburbs were discovered in St. Louis Canyon, one of the many natural wonders at Starved Rock State Park, near Utica in Illinois. They had planned to go on a four-day trip to the Park to hike and take pictures of the scenery. The three women had been sexually assaulted during a short hike to take some photos of the area and brutally killed by blunt force trauma with a piece of wood.

An employee from the nearby Starved Rock Lodge was arrested for the murders six months after the killings and imprisoned until 2020. But was it him or other perpetrators? The debate has raged for 60 years.

What is and where is Starved Rock State Park

St. Louis Canyon in Starved Rock State Park

Starved Rock State Park is located just southeast of the village of Utica, in Deer Park Township, LaSalle County, in Illinois, along the south bank of the Illinois River. It is 2,630 acres with eighteen canyons with vertical rock walls, sandstone bluffs, and access to waterfalls. A flood from a melting glacier, known as the Kankakee Torrent, which took place approximately 14,000–19,000 years ago, led to the topography of the site and its exposed rock canyons.

Before European contact, the area was home to Native Americans, particularly the Kaskaskia. Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette were the first Europeans recorded as exploring the region, and by 1683, the French had established Fort St. Louis on a large sandstone butte overlooking the river they called Le Rocher (the Rock).

Later, after the French had moved on, according to a local legend, in the 1760s, Chief Pontiac of the Ottawa tribe was attending a tribal council meeting. At this council, an Illinois Confederation brave (also called Illiniwek or Illini) stabbed Chief Pontiac. As a result, the Illinois were pursued by the Ottawa and Potawatomi and fled to the butte in the late 18th century. After many days, the remaining Illinois died of starvation, giving this historic park its name – Starved Rock. As their numbers decreased from starvation, desperate warriors attempted to escape, only to be slaughtered in the surrounding forests.

In 1835, Daniel Hitt purchased the land today occupied by Starved Rock State Park from the United States Government as compensation for his tenure in the U.S. Army. He sold the land in 1890 to Ferdinand Walther and developed the land for vacationers. He built a hotel, dance pavilion, and swimming area. In 1911, the State of Illinois purchased the site, making it its first recreational park. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps placed three camps at Starved Rock State Park and began building the Lodge and trail systems you can now witness here at the Park.

In 1966, Starved Rock State Park was named a National Historic Landmark. Starved Rock State Park’s Lodge and Cabins were listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on May 8, 1985, as part of the Illinois State Park Lodges and Cabins Thematic Resources Multiple Property Submission.

The trip to Starved Rock Park

On Monday, March 14, 1960, Mildred Lindquist, 50, Lillian Oetting, 50, and Frances Murphy, 47, left their homes in Riverside, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, and made the hour-and-a-half drive (around 90 miles) for a four-day holiday at Starved Rock Park. They planned to stay at the Starved Rock Lodge in Oglesby, Illinois.

All three women were very close; they were all married to prominent businessmen, and they all attended the Riverside Presbyterian Church. Lillian, who had spent the previous few months nursing her husband after a heart attack, was especially looking forward to the trip to this beautiful part of Illinois.

They arrived at the lodge, where they had two rooms booked and parked up to unpack their luggage, and after checking in, they had lunch in the dining room.

After this, they decided to head off for a short hike in the light snow, as it was a lovely day. Eventually, they came to the dead-end of St. Louis Canyon, with steep rocky walls and a frozen waterfall after a mile or so of walking. Lillian took several pictures of the canyon using Frances Murphy’s camera. Then things went wrong as they encountered someone who tragically ended their trip.

The women go missing

That evening, Lillian’s husband, George, tried to telephone her at the lodge as she had promised to call him but had failed to do so. He was told by staff on duty at the desk that his wife was not answering and was away from her room. The staff member suggested that she would call back in the morning. George was eager to hear how the women’s road trip had gone and if they were settling in well for their stay.

On Tuesday morning, George called the lodge again and asked to speak to his wife for the second time. The hotel receptionist who answered his call mistakenly told him that the three women had been seen at breakfast and were simply out of the lodge at that time. The receptionist said he would send someone up to Lillian’s room to leave a note for her to call him, and so a bell boy for the lodge went up to the room with a card to hang on the doorknob. It’s unclear from reports what exactly the message said but it was something to the effect of you having a message downstairs, and George has been calling.

That night, a winter storm hit the area, and several inches of snow covered the area.

The fact that George couldn’t get a hold of Lillian concerned him. So, he decided to call the other husbands to see if they’d spoken with their wives. The men told George they hadn’t heard from their wives since the three women left Chicago on March 14. At that point, the three men decided to call the lodge back the following morning.

So George telephoned the lodge yet again on Wednesday morning, but again, he could not speak to his wife. At his insistence, employees entered the women’s rooms and found that the beds and bags were unmade. Their Murphy station wagon was also in the parking lot, so they hadn’t left the Starved Rock Lodge.

As soon as George was informed that his wife and the other women were not at the lodge, he called his longtime friend, Virgil W. Peterson, the operating director of the Chicago Crime Commission. When Peterson learned of the news, he contacted the state police and other law enforcement agencies in the area, including the LaSalle County Sheriff’s office. Sheriff Ray Eutsey began organizing search parties to look for the women, and he accompanied one of the groups that left immediately for the park.

Bodies found

As part of the search for the three women, a group of young men from a nearby youth camp set out on the snow-covered trails and rocky terrain on March 16, the weather conditions had deteriorated over the past two days, so the searchers walked on narrow snow and ice-covered trails.

Shortly after the search began, the group found the bodies of three women tucked into a cave in an area of the park known as St. Louis Canyon, about a half-mile away from Starved Rock Lodge. The victims had their skulls smashed in, and there were trails of blood found on the ground and in the snow around their bodies.

Immediately after their bodies were found, Chief William Morris called investigators from the Illinois Bureau of Investigations to help search the cave for clues and determine if any of the victims had been sexually assaulted. The crime scene indicated sexual assaults had occurred. Except for the floor of the overhang where the bodies were found, the entire canyon was covered in nearly six inches of snow. Because snow had fallen in the area, investigators had to disturb the crime scene with flamethrowers and brooms, damaging potential evidence at the crime scene.

The three women were found lying side-by-side, partially covered with snow and covered with blood. They were on their backs, under a small ledge. Mildred and Lillian had their pants and underwear removed. Their clothing had been torn in several places, and their coats had been placed between their legs. All three women had their legs spread open. Each of them had been beaten viciously about the head, and two of the three bodies were tied together with heavy white twine. Frances appeared to have been bound the same way, except the twine around her ankles was undone. A trail of blood leading from the bodies indicated that the bodies had been dragged and positioned under the rock ledge.

The Starved Rock Murders - murder weapon

Binoculars covered with blood were recovered from the scene, as well as Frances Murphy’s Argus C3 camera, which was found about ten feet from the bodies of the women with a broken strap and its leather case was smeared with blood. The strap on the device was completely broken, which made authorities believe it had been ripped away from her, and the strap snapped in the process.

Subsequent processing of the film from the camera showed that the women had taken several pictures on their hike. Most images showed them posing in front of the various waterfalls and rocks in the canyons. The last picture on the roll was a triple exposure, meaning that the knob on the top of the camera hadn’t been rotated before taking the photo. The picture showed Frances and Mildred standing in front of a frozen waterfall, and the image was overlaid onto another frame of film at a location close to the cave where their bodies were found.

The LaSalle County Sheriff’s Office thought that the final picture contained the outline of a man’s face in a shadow between the rockface of Saint Louis Canyon and a tree trunk behind where Mildred was standing. After plenty of investigation into this phantom shadow, authorities ruled out the theory that the women had photographed their killer.

A short distance away from the bodies, LaSalle County’s States Attorney Harland Warren came across a frozen three-foot tree limb that was streaked with blood and the snow beneath it was covered with blood. They also found a long icicle from the cave with blood on it. The detectives quickly realized that these were likely to be murder weapons.

Chief William Morris told reporters that he believed it would have been very difficult for one person to overpower and kill all three women who’d put up a fight. If it was one person, it was likely a man who was strong enough to overcome three victims at once. Mildred, Lillian, and Frances were fit for their age and were not frail.

Although there was some blood found inside the cave and on the walls, there was not the amount that you’d expect to see if the cave was the site where the women had been killed. State police believed that the killer may have murdered the women in a clearing somewhere else in the woods and left them there, and possibly returned to drag their bodies into the cave to prevent someone else from finding them.

Autopsies

The bodies were taken to the Hulse Funeral Home in Ottawa, where they were examined and autopsied. The women had been sexually assaulted, but the coroner failed to find any evidence of rape. The doctors were able to determine the time of death, placing it shortly after they had lunch at the lodge.

Investigations

The investigators quickly dismissed robbery as a motive for the terrible murders, as the women had left most of their valuables behind in their rooms when they went for their afternoon hike. Their rings and other personal possessions were still on the dead bodies.

Harland Warren was in charge of the investigation, but the state police maintained their authority in the case because the murders were committed on park property. The LaSalle County sheriff had no experience dealing with these types of crimes.

A set of keys was found on the trail leading to the cave, and there was a sighting of a grey station wagon seen in the area where the women entered the park shortly before they were suspected of being killed. But these clues led nowhere. The continued media coverage of the case kept the pressure on the police officials to make progress.

Virgil Peterson, who worked for the Chicago Crime Commission and was close friends with all three victims’ families, criticized the LaSalle County Sheriff’s office for not organizing a search sooner for the women. He told reporters that two days had passed with no sign of the women before any effort was made to find them. He said that when multiple attempts by the victims’ husbands on Monday and Tuesday went unanswered, that should have been an indication that something had happened to them. Peterson also criticized the fact that there was no police presence in the park to help prevent a crime like this from happening in the first place.

The total man-hours put into solving the murders up until that point was totaling close to 22,000 hours with a $65,000 cost. So, with funds drying up, solving the murders was becoming a distant hope.

The twine

Using his own money, Harland Warren purchased a microscope and began studying the twine that had been used to bind the women. It revealed that there were two kinds of twine used, a 12 as well as a 20-ply cord.

Deputies Bill Dummett and Wayne Hess began a search for the particular twine at the Starved Rock Lodge. In September 1960, Warren and his deputies met with the manager of the lodge’s kitchen and within a short time, both kinds of twine were discovered and used for wrapping food. The deputies used the lodge purchasing records to identify the twine’s manufacturer. The killer either worked at or had access to the park’s lodge kitchen area. But at that point, polygraph tests of the employees had all come up negative.

Chester Weger as a suspect - was he the Starved Rock Murderer?

Warren hired a specialist from a prominent Chicago firm and recalled all of the employees who had worked during the week of the murders on September 23, 1960. One by one, they came to a small cabin located near the lodge and had the repeat polygraph test. Then, Bill Dummett brought in a former dishwasher named Chester Otto Weger.

When Weger’s polygraph test was completed, Warren noticed that the examiner’s face had gone pale. As soon as Weger left the cabin, the technician turned to Warren and the two deputies and said, “That’s your man.”

21-year-old Chester Weger was married and had two young children. He had worked at the park until that summer when he resigned to go into business with his father as a house painter. Dummett remembered the man’s name from an earlier police report, but investigators had not considered him a suspect. He had shown up to work on March 15th with some scratches on his face that appeared to be fresh. At the time, Chester told the police that he had accidentally cut himself shaving and during the afternoon of the murders, he was in his room in the basement writing letters.

Weger handed over a piece of a buckskin jacket that he owned so that some suspicious “dark stains” on it could be examined, which were confirmed as blood. Whether it was animal or human blood was disputed in subsequent events.

Three days later, on September 26, Chester took four more polygraph tests.

Once the jacket was determined to be stained with blood, Warren put Weger under constant surveillance by the state police. Warren, along with Dummett and Weger, began checking into Weger’s past and also into similar crimes in the area.

Authorities discovered that roughly six months before the murders in Starved Rock State Park in 1959, two high school seniors on a date in nearby Matthiessen State Park had been robbed at gunpoint while getting into their car. In that case, the couple reported the crime to authorities and told them they were tied up by a man with a rifle in the woods and had been hiding in the shadows of a trailhead parking lot. He had robbed them and sexually assaulted the young woman. When the victims first went to the LaSalle County Sheriff’s Office to report the severe incident, deputies did not believe them and dismissed their story as fiction.

With Warren’s approval, Dummett found the young female victim, and with the help of some pictures, she quickly identified Chester Weger as the assailant.

Despite this positive ID, Warren waited to charge Weger, partly because of his impending re-election and the fact he might be accused of arresting Weger as a publicity stunt. So he left Weger under surveillance. Warren then lost the election by nearly 3,500 votes.

For October 1960, police kept Chester under 24-hour surveillance as he went to and from work and lived with his wife and their two small children.

After the election result but before his replacement was in office, on November 16th, 1960, police used the woman’s positive ID of the Matthiessen State Park incident as a means to arrest Weger for the sexual assault and robbery. Hess and Dummett were ordered to arrest him, believing Weger would confess to the crime and to the Starved Rock murders.

Warren made careful plans with his two deputies about how to interrogate Weger before confronting him with the murder charges. When Hess and Dummett arrived at Weger’s apartment, they told him they were taking him to ask a few questions and didn’t formally charge him.

But once Weger was in custody, the officers began to question him about the rape and then the murders. They kept him in the interrogation room until past midnight, and then fatigued by all the questions, Weger stopped in mid-sentence and asked to see his family. A police car was dispatched to his parents’ home in Oglesby and they were brought in. Dummett and Hess gave them a few minutes alone with their son.

The next day, on November 17, Deputy Hess stated, “When Bill stepped out of the back room in the state’s attorney’s office to show Mr. and Mrs. Weger to the door so they could go home, I could see that something was bothering Chester. I said, ‘Chester, why don’t you tell me about it? There are just the two of us here… just tell me about it.’ He said, ‘All right. I did it. I got scared. I tried to grab their pocketbook, they fought, and I hit them.’ The pocketbook that Weger claimed that he tried to take was actually the camera. The confession was transcribed and signed by Weger.

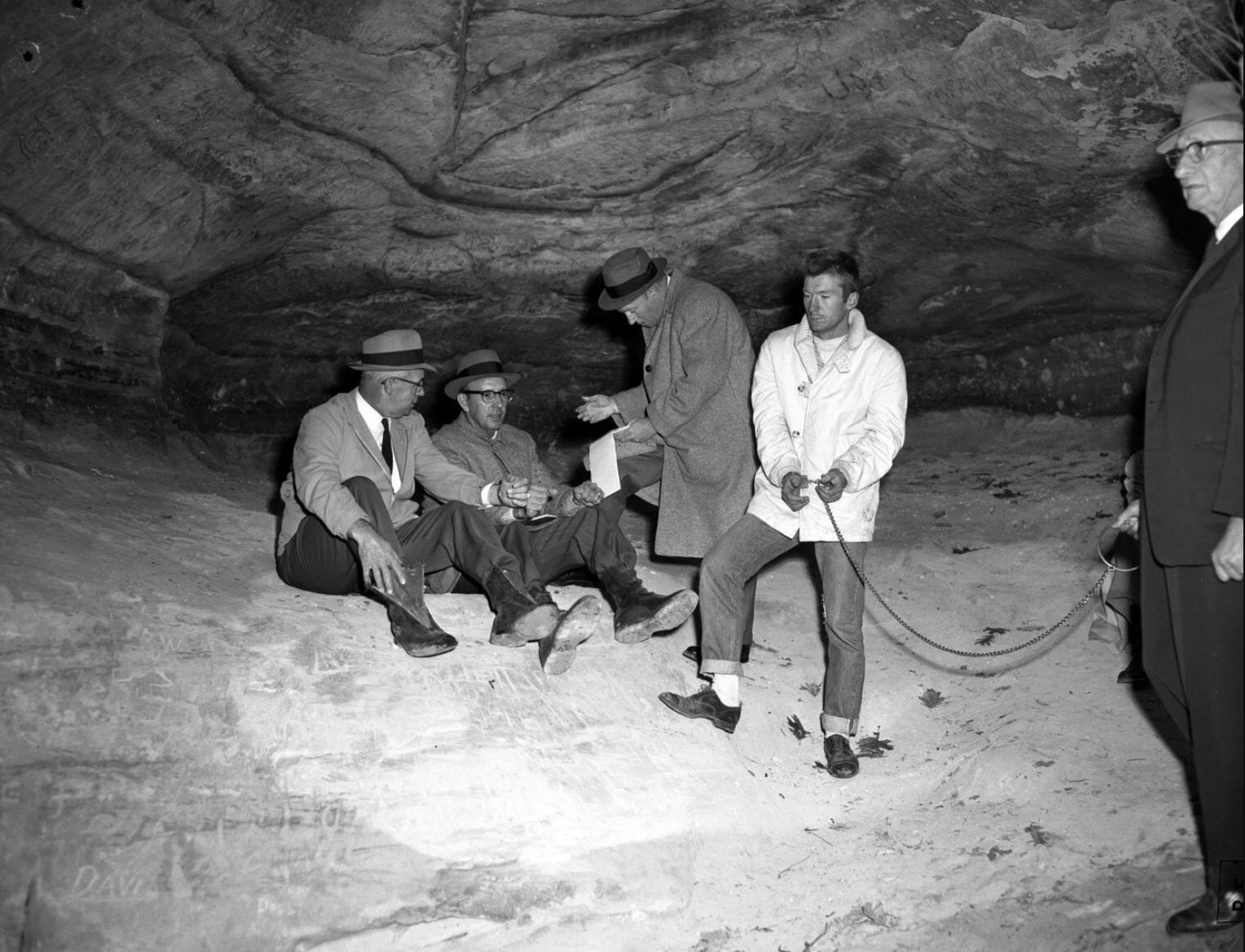

Reenactment of the Starved Rock Murders by Chester Weger

The next day, Weger accompanied state police to St. Louis Canyon for a reenactment of the murders with a large group of newspaper and radio reporters.

He said that on the day the three women were in the Canyon, he’d been on a mission to rob someone. When he saw them, he attempted to snatch one of their purses, but when he grabbed what he thought was a purse strap on Frances Murphy’s shoulder, it broke, and he realized it was the strap to a camera. He begged the women to go further into the canyon and give him time to escape. He said the women agreed to this request and walked away deeper into the canyon.

Weger then apparently decided to continue stalking the women. Near the end of the canyon, next to a cave, he jumped out of the woods and threatened them again with a large tree limb and told them to move into the cave, after which he tied them up with some twine he’d stolen from the kitchen at the Starved Rock Lodge.

He said he originally planned to leave them in the cave, but as he was leaving, Frances broke free and ran after him, threatening him with her binoculars, attempting to strike him on the back of the head, but the strap broke. Weger then said he picked up the tree limb and struck Frances on the back of her neck and dragged her body back to the mouth of the cave, where Mildred and Lillian were, and found that they had been able to stand upright despite their bindings. He said they too, came after him and began trying to claw at his face. He realized the situation was out of his control, and he could not leave any of them alive.

He told reporters and police that all three victims begged for their lives as he beat them to death with the frozen tree limb. He said after the attack, he checked all their pulses to ensure that they were dead.

During the confession, when he was asked why he had dragged the bodies under the overhang in St. Louis Canyon, Weger said that he had spotted a small aeroplane flying low over the park. Weger said that he was afraid that it was a state police plane, so he moved the bodies so that they could not be seen from above. Police later followed up on that detail and confirmed that a pilot flying a red and white aeroplane out of nearby Ottawa Airport had been over Saint Louis Canyon on the afternoon of March 14th.

Chester continued to show reporters and police his reenactment of the crime and said before leaving the area, he partially undressed Mildred and Lillian to make the scene appear as if a sexual predator had committed the murders. He then washed his hands with a scoop of snow and went back to Starved Rock Lodge to begin his dishwashing shift at five o’clock.

None of the three victims’ jewelry or purses had been taken after they were murdered. When police asked Chester to explain why he hadn’t robbed the women of those items, if robbery was his sole motive, he didn’t directly answer the question. He replied, “It all started with robbery, but I don’t know what I needed the money for.”

Then, three days after his first meeting with his court-appointed attorney, On November 19. 1960, Weger changed his story and said that he was innocent of all of the charges, that he had been in Oglesby at the time of the killings and had been duped and coerced into the so-called confession. He said that Dummett and Hess had threatened him with violence, so he had been so scared that he signed the papers. Weger also said that Dummett had fed him the information about the aeroplane.

The trial of Chester Weger

On November 18th, 1960, a grand jury in LaSalle County indicted Chester for three counts of first-degree murder and eight other felonies related to the 1959 sexual assault and robbery of the high school couple in Matthiessen State Park. Some of his other felonies were for purse snatching in another state park and molesting a woman and her children.

Weger’s trial began on January 20, 1961, presided over by Judge Leonard Hoffman with the threat of the death penalty. The new state’s attorney, Robert E. Richardson, was the lead prosecutor and Anthony Raccuglia assisted him. Because Richardson and Raccuglia had never tried a murder case before, it was suggested that Harland Warren would be a special prosecutor for this case only. But Richardson, who had strongly criticized Warren during the election, dismissed the idea. Richardson and Raccuglia decided to file charges against Weger for only one of the three murders, Lillian Oetting, as, in the event of a mistrial or an acquittal, they could still file charges against him for the other killings.

Weger’s lawyer maintained that his client was innocent and that police had bungled the investigation from the start. He claimed the state was prejudiced, and prosecutors had no credible physical evidence linking him to the crimes. But the prosecution successfully won a motion to allow the confession as evidence despite the defense trying multiple times to get it thrown out. However, the defense team successfully argued that the jurors not be allowed to see all of the crime scene photos. Most notably, images of the three women’s bodies and their wounds.

During the trial, the judge only allowed prosecutors to show the jury one photo of the victims in the cave. The defense claimed that the photos in their totality were “inflammatory and would prejudice the jury against the defendant”

Investigators then admitted that the state lab had made an error in identifying the bloodstain on Weger’s jacket as being from an animal. Before trial, investigators had sent the jacket to the FBI’s lab in Washington and the results that came back concluded the stain on the jacket could be human blood but the FBI’s experts couldn’t rule out animal blood for sure due to the tanning process used to make the leather. The FBI agent who testified at trial said it appeared someone had tried very hard to wash the stain to remove whatever blood had soaked into it.

Weger was put on the stand for over three hours, where he maintained his innocence and claimed the deputies from LaSalle county threatened him into confessing to something he didn’t do. The trial in the end lasted five weeks.

The jury deliberated for nearly ten hours and then on Friday, March 3rd, 1961, the jury found Chester guilty of Lillian Oetting’s murder and sentenced him to life in prison. According to Illinois law at the time, he was eligible for parole after serving 20 years of that sentence and the death penalty was rejected.

After Judge Hoffman dismissed the jurors, reporters asked them if they knew that a life sentence in Illinois meant that Weger would be eligible for parole in a few years. The court did not inform them.

Chester Weger was imprisoned at the Statesville Penitentiary in Joliet and was denied parole after he was first eligible in 1972.

Weger appealed the conviction and requested a fresh trial as a juror from the first trial co-signed the affidavit and suggested that LaSalle County Deputies pressured the jury into finding him guilty. The juror was willing to testify that the rules of trial procedure were violated in the first trial.

The state then announced it was going to try Weger for Frances and Mildred’s murders.

In 1962, the Illinois Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s decision and did not grant him a new trial. In February 1963, LaSalle County was forced to drop all charges for the 1959 rape and robbery in Matthiessen State Park.

In April 1963, a new state attorney in LaSalle County dropped the remaining murder indictments of Frances and Mildred’s murder because there was reluctance from the Illinois state legislature to impose the death penalty.

Weger wrote a 48-page letter in prison and in it, he claimed he was framed for the Starved Rock murders and went into detail about how authorities coerced him to make the false confession. When reporters queried the previous convictions for rape and theft prior to 1960, he claimed in those incidents, police had gotten him to confess as well falsely.

In 2004, Chester Weger’s attorneys attempted to have new DNA testing done on items of evidence. They hoped advancements in DNA technology would prove that the blood on the jacket and the hairs found clutched in one of the victims’ hands would not link him to the murders.

Unfortunately, LaSalle County had allowed school groups, civic clubs, and journalists to handle and examine key pieces of evidence in the case while it was in storage over the 43 years since the conviction and the DNA had become contained. The judge ruled against having DNA testing done in the case due to the potentially tainted evidence.

In 2007, 2016 and 2018, Chester again applied for parole and was denied. When asked if he would be willing to admit to having remorse for the crime he was convicted of in exchange for his freedom, Chester said, “I’ll stay in prison the rest of my life to prove my innocence before I’ll make any deal with any of you crooked people.” Clemency petitions were sent to the state Governors over the year, including Rod Blagojevich, in June 2007, but these were denied

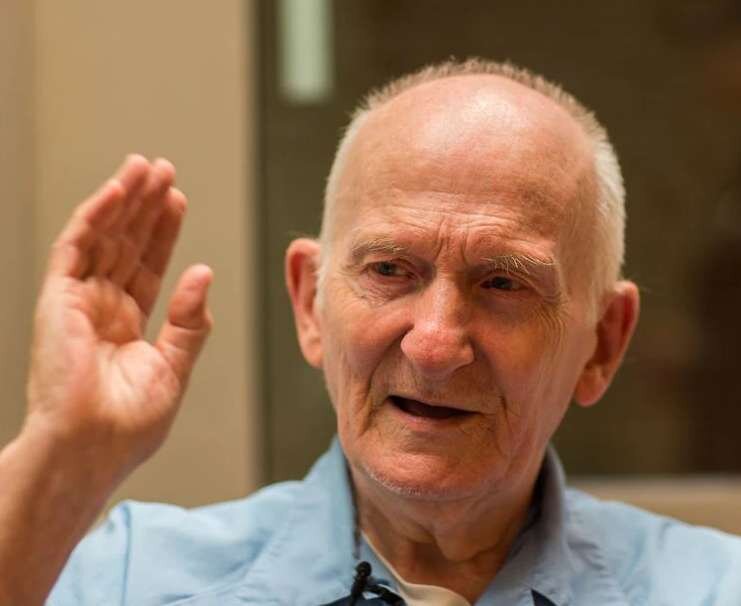

On November 21, 2019, on his 24th request, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board finally granted parole to Weger by a vote of 9–4, 58 years after his conviction.

The release of Chester Weger

On February 21, 2020, Chester Weger was released from Pinckneyville Correctional Center in far southern Illinois at the age of 80 by the Illinois Department of Corrections after he was granted parole in November 2019. After he was released, he went to Leonard’s Ministries, a Chicago rehabilitation center.

“They ruined my life,” Weger said shortly after he walked out of prison,

”They made millions of dollars off of me off of publicity by keeping me locked up 60 years for something I never done.”

Weger said he was looking forward to living the rest of his life with his family. “It’s wonderful, just to be able to be out and be with my friends again, my relatives”.

In 2010, Weger was asked: “Why not show some remorse – say you did it even if you didn’t and get out?” Weger replied: “Why should I feel remorse then if I never killed them? I mean, I feel sorry for the people being dead, but I’m not going to admit that I done something I never done.”

In a 1981 interview, he said, “The deputy already had a confession already drawn up, and he threatened me with a pistol. He told me, he says, ‘You either sign the confession, or I’ll kill you and say that you try to escape.”

Timeline of Events

11/16/1960 Chester Weger arrested for the Starved Rock Murders

11/17/1960 Confession to the murders

11/19/1960 Weger recants his confession

01/20/1961 Criminal trial commences

02/27/1961 Chester Weger testifies in his own defense

03/03/1961 The jury finds Chester Weger guilty

04/03/1961 Chester Weger is sentenced to life in prison

11/21/2019 Parole granted

02/21/2020 Weger released from prison

Was Weger really guilty?

Some believe that there are many factors that cast doubt on Chester Weger’s confession and subsequent conviction for the murders. These include:

There was no physical evidence linking him to the scene of the crime and no witnesses place him there

A blond hair found on the finger of Frances Murphy’s glove was analyzed by the Eastman Kodak company and found to be dissimilar to hair samples taken from Weger.

Black hairs were found in the palm of Lillian Oetting, which was not Weger’s hair color.

It is unlikely that Chester Weger would be able to overpower and restrain all three women alone. Did an accomplice help him?

A Chicago police sergeant, Mark Gibson, submitted an affidavit in 2006 that recounted the confession. It was being used in court to support a motion for new DNA tests in the Starved Rock murder case. In the affidavit, Gibson stated that he and his partner, now deceased, were called to Rush–St. Luke’s Presbyterian Hospital to see a terminally ill patient who wanted to “clear her conscience.

The affidavit said, “The woman was lying in a hospital bed. I went over toward her, and she grabbed hold of my hand. She indicated that when she was younger, she had been with her friends at a state park when something happened.” The woman then told Gibson that she was at a park in Utica and things “got out of hand,” multiple victims were killed, and “they dragged the bodies.” Gibson said that the woman’s daughters cut the interview short and told the police to leave the room.

The affidavit did not state whether there had been a follow-up or why the confession was not presented until 2006. The alleged “confession” was not allowed into the court hearings, although new DNA tests were ordered. However, they failed to clear Weger of anything because the samples had been corrupted over the years.

Exclusive articles for members of StrangeOutdoors that are not available elsewhere on the site.

See the list of Exclusive members-only articles on StrangeOutdoors.com

Read other true crime stories from StrangeOutdoors

Shocking camping abductions and murders

The horrific rape and murder of Sophie Louise Hook whilst camping in her Uncle's garden

Robert Hansen “Butcher Baker” - the Alaska Serial killer who hunted his victims in the wilderness

The miraculous escape of the Brazilian and German backpackers at Salt Creek in South Australia

Further viewing

Sources

https://www.starvedrocklodge.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Starved_Rock_State_Park

Park Predators Podcast season 2 “The Housewives”

https://www.americanhauntingsink.com/the-starved-rock-murders

https://chicago.cbslocal.com/2020/02/21/convicted-starved-rock-killer-chester-weger-released-from-prison/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester_Weger

https://www.halemonico.com/a-hale-news/chester-weger-and-the-starved-rock-murders/